submitted by Jennie Burrows

I never met my great-aunt, but I am proud to be honouring her remarkable life. At the age of 2, Gertrude Jane Burrows was taken across the seas from England to Australia, accompanied by three older brothers, her father James, and her heavily pregnant mother Rosina. As the boat was landing at Fremantle in June 1886, her mother bore a baby girl whom she named Oriana, after the name of the ship. Gertrude’s earliest memories would have been of a strange land (Fremantle was described as “a city of public houses, flies, sand, limestone, convicts and stacks of sandalwood”), a newborn sibling, and a very sick mother who died a month later from the complications of childbirth. Oriana died shortly afterwards at the age of 5 months.

Six months after the death of Rosina, James married Emma Taylor, a widow with two children who had also been aboard the Oriana. Little is known of the “Brady Bunch” life of the six children, except that James’ descendants said that Emma was harsh.

When Gertrude was 16, she sailed back to England with her father, perhaps because James’ mother had died. During their 3 years stay in England, Gertrude worked as a servant in Bedford, close to where she was born.

Gertrude and James returned in 1903 and Gertrude began a career as a laundress. This proved to be a useful occupation as, in 1906, at the age of 22, Gertrude had her first child, William Horace Meredith Burrows. A laundress was generally able to keep her child with her rather than hand over to someone else to raise.

There is no information on William’s father. The father’s name does not appear on the birth certificate, and when William married, the marriage certificate said “father unknown”. The English custom of using the unacknowledged father’s name as the child’s middle name suggests that a man in town named William Edward Meredith may have had contact with Gertrude.

In 1907, Gertrude worked as a laundress at Fremantle Hospital for the Insane. There had been much press about the poor conditions in lunatic asylums, and patients were being transferred to a new facility at Claremont whilst Gertrude was at Fremantle Asylum. At this same time, James and Emma’s marriage appeared to have broken down with James publishing in the local paper: “I will not be responsible for any debts contracted by my wife after this date”. In fact, when Emma died just two years later, there was no reference in the death notice to her husband or step-children.

In 1908, Gertrude made headlines when the police charged a nurse, Mrs Tonkin, with the crime of carrying out an abortion. The trial has been summarised as follows:

By the 24th of April, one month following the alleged abortion, Gertrude Burrows was sufficiently recovered from her ordeal to face the preliminary hearing of the case. She testified that she had gone to Mrs. Tonkin for the purpose of having an abortion; Tonkin professed herself nervous about doing it but agreed on the condition that Gertrude tell no-one. She performed the operation and told her to return in a few days if she was not well. Three days after the operation, Gertrude suffered a miscarriage, but did not recover as expected. She haemorrhaged and experienced high temperatures and was eventually seen by a doctor of the Asylum who contacted the police.

During the Supreme Court trial, Tonkin’s husband returned from the mines and he and Tonkin’s companion Ethel sat beside her during the trial. The jury decided that there was not enough evidence to uphold a conviction and returned a verdict of not guilty. The fact that Tonkin was a good looking woman, well supported and with an aura of respectability, may have encouraged this finding. Regardless of the fact that her mother was a convicted abortionist and that numerous women visited her house, Tonkin was given the benefit of the doubt, suggesting that chivalrous treatment is more likely to be proffered to respectable women.

The following year Gertrude moved to Geraldton, 400 kilometres north of Perth, where she was to reside for the rest of her life. In 1910, she gave birth to her second child Dorothy Rose Burrows, again father unknown. Later that year, the European Steam Laundry opened in Geraldton. Laundry work was hard:

Shirts, collars, and the like, are of course ironed by hand. For this purpose an iron-heater has been provided. On this apparatus, which is really an enclosed furnace, about a dozen irons can be heated at the same time. This department is in the charge of Miss Burrows, who is regarded by those who know her work, as an expert laundress.

The Steam Laundry changed owners 6 months later and the new owner sacked Gertrude with no notice. Gertrude sued him for her rightful wages and the Bench agreed that as she was paid each Saturday, this constituted a weekly contract, terminable with a week’s notice, and gave a verdict in her favour for the full amount plus costs.

In 1912, Gertrude gave birth to her third child Frederick, who was nicknamed Blue due to his red hair. The following year, at the age of 29, Gertrude gave birth to her fourth child Robert, who also had red hair. The father is unknown in both cases.

Gertrude was taken to court in January 1921 by the owner of the Shamrock Hotel who claimed she was in the unlawful possession of some of their items, however the Magistrate held there was no evidence and dismissed the charge.

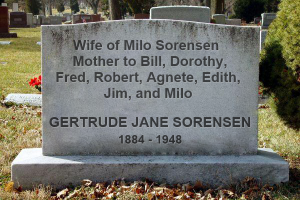

At some point Gertrude met Milo Sorenson, a handsome Norwegian who had arrived in Geraldton in 1911. In 1921, Gertrude (37) married Milo (32) bringing four children to the marriage: William (15), Dorothy (11), Frederick (9) and Robert (8). Gertrude went on to have another four children with Sorenson: Agnete (1921), Edith (1923), James (1924), and Milo (1925).

Gertrude died 21 March 1948 at Rosella Hospital in Geraldton, a woman ahead of her time.